Cover photo by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

By Megan Sumeracki

In my last blog, I wrote about cognitive networks and implicit bias. The gist of the post was that our systems allow us to categorize and generalize, flexibly and automatically, and that this generally helps us. For example, we have some general rules about what a chair is, and a prototype for chairs. We can walk into a room we have never been in before and identify chairs we have never seen before, and we can do this very quickly. The problem, of course, is that we don’t just do this with chairs or other inanimate objects. We also do this with people.

Our experiences of what we see and hear ourselves out in the world, what we read, what we watch on screen, and what we are told are all integrated into our cognitive networks. We develop implicit bias, and this is true even if we consciously reject the stereotype, and whether we like it or not. For this reason, exposure to diversity matters.

In today’s post, I cover a research article that was published in Psychological Science, a prestigious peer-reviewed journal, by Yair Bar-Haim, Talee Ziv, Dominique Lamy, and Richard Hodes (1). The authors note previous research demonstrates that children as young as 4 years old already display racial stereotyping, and these kids also show a recognition advantage for faces that match their own race.

The study published by Bar-Haim and colleagues demonstrates that exposure to diversity in very young babies matters. They recruited 3-month-old infants that came from three distinct populations, and these populations varied in terms of how much exposure they had to different races.

One group of babies were recruited from Israel. They were white, and their caretakers were largely white.

Another group of babies were recruited from Ethiopia and were awaiting immigration to Israel. They were black, and their caretakers were primarily black.

A third group of babies were recruited from absorption centers in Israel. These babies were from Ethiopia, but had very recently immigrated to Israel. According to the authors, many new immigrants live in absorption centers when they first move to Israel. These babies were black and would have experienced a lot of cross-race exposure. For example, they receive a lot of social support in these centers, and these service providers are largely white. Further, there are a lot of other white immigrant families in these absorption centers.

Therefore, across the three groups, we have two groups where the race of the baby matches the race of the environment, and one group where there are many people, and even caretakers, in the environment that are diverse, and do not always match the race of the baby.

(An interesting related but slightly tangential nugget of information: In writing this piece, I consulted with a friend who is expert in identity theories. The authors in the referenced study used the term “Caucasian.” I remembered that the term was problematic, but would not have been able to explain to someone else exactly why. Further, if I was going to replace the term, I wanted to ensure I did so accurately and appropriately. When I asked my friend about it, they gave me a fascinating lesson on the term and labels that various groups have endorsed in different regions and throughout history. I learned that the term “Caucasian” comes from an 18th century anthropologist, Johann Blumenbach. He used the term to describe a skull that was found in the Caucasus Mountains region, calling the skull the most beautiful human skull. It was larger than others he studied, and this was assumed to signify that these people were superior because they must have had larger brains than others. He labeled these people Caucasians and identified them as representing the ideal human form, the top of a racial hierarchy. Caucasian is now used synonymously with “white European,” and implies that white Europeans are the ideal human form. I don’t begrudge the authors of the study cited here (1) for using the term; their article is from 2006, and it is a term that is still pervasive in some disciplines (see this editorial by Luwi Shamambo and Tracey Henry from 2022, 2). Still, I wanted to avoid using the term and thought other educators might be as interested as I was to learn the historical roots.)

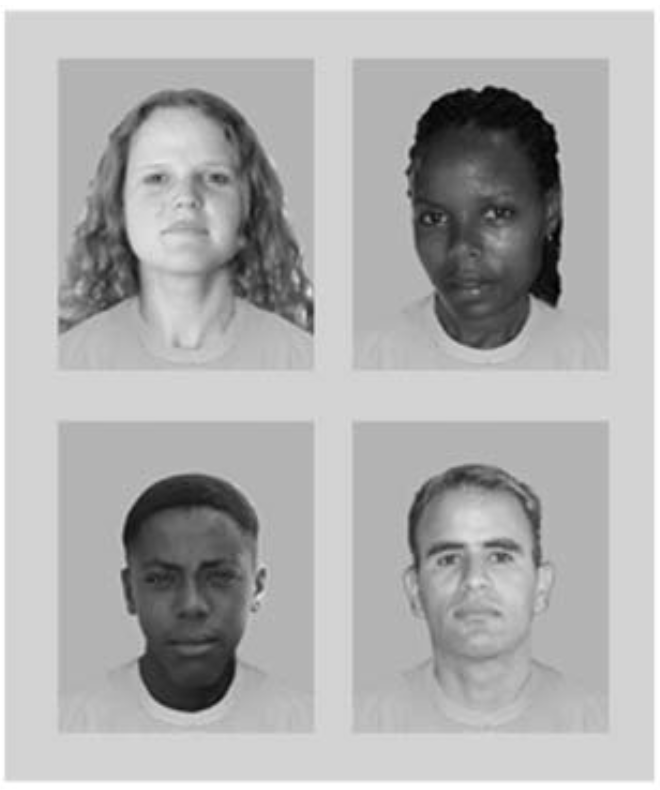

Image from Bar-Haim et al., 2006 (1)

The authors used a standard visual preference task. The 3-month-old babies were shown pairs of faces, one white and one black, and the researchers measured where the babies looked.

The researchers found that the babies in the first two groups spent more time looking at the faces that most closely matched their own race, and that of their caretakers. In other words, the white babies looked more at the white faces, and the black babies looked more at the black faces. Babies as young as 3 months can show a preference for their own race. However, the third group, black babies with large exposure across races in their environment, showed no preference for either type of face. They spent roughly the same amount of time looking at each face. When babies were living in environments that exposed them to the other race, they did not show a preference for their own race.

Even for very young babies, and certainly as we continue to grow up and build our cognitive networks, exposure to diversity matters. Personally, as we raise our daughter, we try to expose her to as many new experiences and perspectives possible. We tell our daughter, isn’t different beautiful? There are so many different ways to live, and yet we are all connected by common human experiences. Implicit bias is in all of us. Pretending we don’t have implicit bias is unlikely to make things better. But certainly, we can try to challenge the stereotypes and try to build more connections.

By Pete Linforth from Pixabay

References:

(1) Bar-Haim, Y., Ziv, T., Lamy, D., & Hodes, R. M. (2006). Nature and nurture in own-race face processing. Psychological Science, 17(2), 159-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01679.x

(2) Shamambo, L. J., & Henry, T. L. (2022). Rethinking the use of “Caucasian” in clinical language and curricula: A trainee’s call to action. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(7), 1780-1782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07431-6